Onshore Oilfield Development: A Complete Guide for Beginners

The world runs on energy, and for the foreseeable future, a significant portion of that energy will continue to come from oil and gas. While offshore drilling often captures the headlines, a vast and vital part of this industry operates on land. This is the world of onshore oilfield development, a complex and fascinating process that transforms a potential resource hidden deep within the earth into the fuel that powers our lives.

This comprehensive guide will walk you through the entire lifecycle of an onshore oilfield, from the initial whispers of discovery to the final stages of responsible closure. We’ll demystify the technical jargon, explore the critical considerations, and provide a clear roadmap for understanding this essential industry. Whether you’re a student, a potential investor, or simply curious about where our energy comes from, this guide is for you.

The Spark of Discovery: Prospecting and Exploration

Every oilfield begins as an idea—a hypothesis based on geological clues that oil or gas might be trapped miles beneath the surface. This initial phase, known as prospecting and exploration, is a high-stakes detective story written in the language of rocks and seismic waves.

Uncovering Earth’s Secrets: Geological Surveys

Geologists are the primary detectives in this initial stage. They begin by studying surface-level features, analyzing rock outcrops, and examining satellite imagery to identify sedimentary basins—large areas where oil and gas are likely to have formed. They also look for more subtle clues, such as natural oil or gas seeps, which can indicate the presence of a petroleum system below.

Listening to the Earth: Seismic Surveys

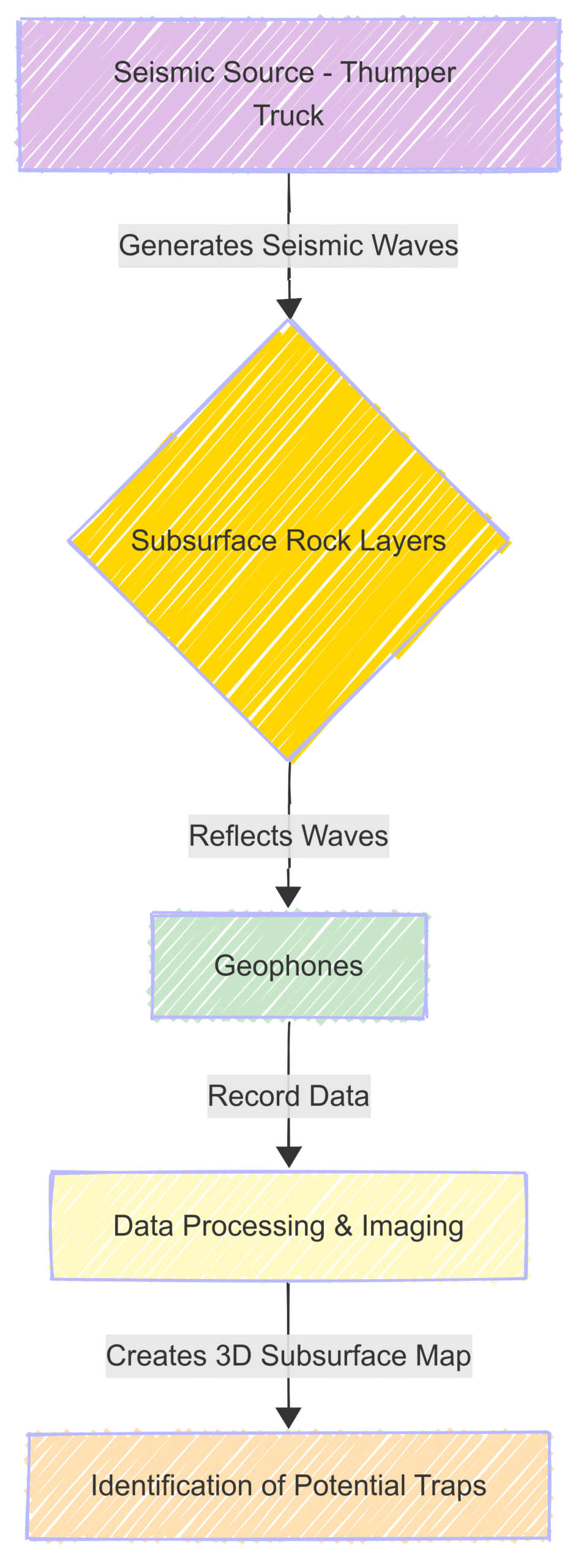

Once a promising area is identified, the exploration team employs a technology called seismic surveying. This process is akin to giving the Earth an ultrasound. Large trucks, known as “thumpers,” generate powerful vibrations (seismic waves) that travel deep into the ground. These waves bounce off different rock layers and are recorded by a grid of sensors called geophones.

By analyzing the time it takes for these waves to return to the surface, geophysicists can create a detailed 3D map of the subsurface geology. This map helps them identify potential “traps”—geological formations where oil and gas could be confined.

The Moment of Truth: Exploratory Drilling

Even with the most advanced seismic data, there’s only one way to be certain if oil or gas is present: drill an exploratory well. This is a high-risk, high-reward endeavor. A drilling rig is brought to the site, and a well is carefully drilled to the target depth, which can be thousands of feet below the surface. As the well is drilled, geologists analyze the rock cuttings brought to the surface for signs of hydrocarbons.

Once the target formation is reached, a series of tests are conducted to determine the presence and quantity of oil or gas. If the results are positive, the exploratory well is a success, and the company moves on to the next phase: appraisal.

From Discovery to Development: Appraisal and Planning

Discovering oil is just the first step. The next crucial phase is to determine if the discovery is commercially viable. This is the appraisal and planning stage, where the potential of the newly found reservoir is thoroughly evaluated.

Sizing Up the Prize: Appraisal Wells

To understand the size and characteristics of the reservoir, additional wells, known as appraisal wells, are drilled. These wells help to delineate the extent of the oil or gas accumulation and provide valuable data on the properties of the reservoir rock (porosity and permeability) and the fluids it contains.

Building the Blueprint: The Field Development Plan

With a comprehensive understanding of the reservoir, the oil company develops a Field Development Plan (FDP). This detailed document is the master blueprint for the entire project and outlines:

The number and location of production wells needed to efficiently extract the oil and gas.

The design of the surface facilities, including pipelines, processing equipment, and storage tanks.

The production strategy, including the expected rate of extraction and the techniques that will be used.

An environmental impact assessment and the measures that will be taken to mitigate any potential environmental effects.

A detailed economic analysis, including cost estimates and projected revenues.

The FDP is a critical document that requires approval from regulatory authorities before any significant development can begin.

The Heart of the Operation: Drilling and Completion

With an approved Field Development Plan in hand, the oilfield moves into the most active and visible phase: drilling and completion. This is where the infrastructure to extract the oil and gas is put in place.

The Dance of the Drill: The Drilling Process

Drilling a production well is a highly technical and carefully orchestrated process. A larger, more permanent drilling rig is assembled on site. The drilling process involves:

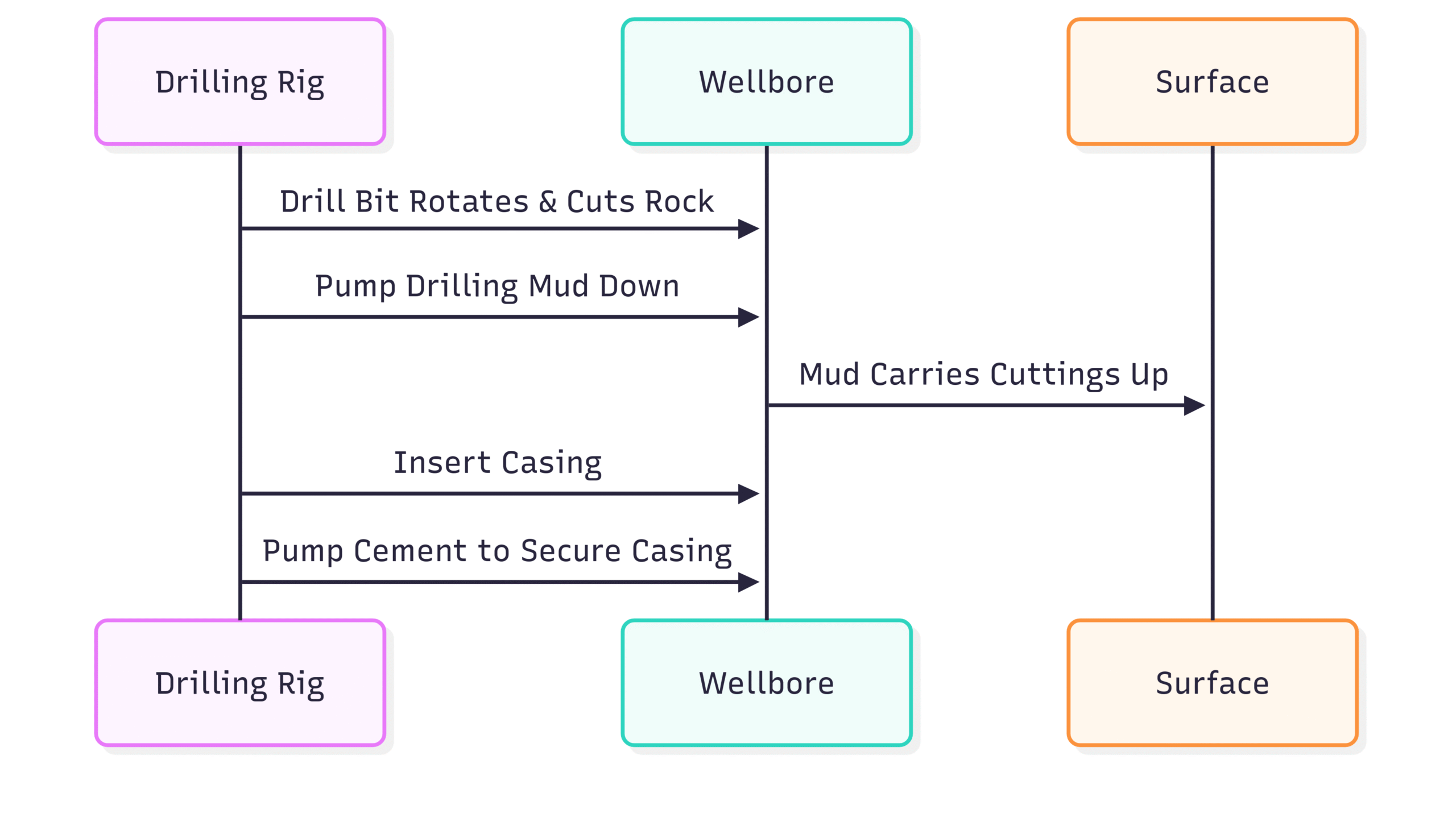

Drilling the Wellbore: A powerful drill bit, attached to the end of a long string of drill pipes, rotates to cut through the rock layers.

Circulating Drilling Mud: A specially formulated fluid, known as drilling mud, is continuously pumped down the drill pipe and back up the wellbore. This mud serves several critical functions: it cools and lubricates the drill bit, carries rock cuttings to the surface, and helps to control the pressure within the well.

Casing and Cementing: As the well is drilled, steel pipes called casing are inserted into the wellbore and cemented in place. This provides structural integrity to the well and isolates the different geological formations to prevent the contamination of freshwater aquifers.

Preparing for Production: Well Completion

Once the well has been drilled to the target depth, it must be “completed” to allow oil and gas to flow into the wellbore and up to the surface. The completion process involves:

Perforation: Small, targeted explosions are used to create holes in the casing and cement, connecting the wellbore to the oil and gas-bearing reservoir rock.

Installing Production Tubing: A smaller diameter pipe, called production tubing, is run inside the casing. This tubing provides a dedicated path for the oil and gas to flow to the surface.

Installing the Wellhead: A complex assembly of valves and gauges, known as a “Christmas tree,” is installed at the surface of the well. This allows for the control and monitoring of the flow of oil and gas.

In some cases, especially in unconventional reservoirs like shale, a process called hydraulic fracturing (or “fracking”) is used to stimulate production. This involves injecting a high-pressure fluid into the reservoir to create small fractures in the rock, allowing the trapped oil and gas to flow more freely.

The Flow of Energy: Production and Processing

With the wells drilled and completed, the oilfield enters its longest phase: production. This is the period during which oil and gas are extracted, processed, and transported to market.

Bringing it to the Surface: The Production Phase

The natural pressure within the reservoir is often sufficient to push the oil and gas to the surface in the early stages of production. This is known as primary recovery. Over time, as the reservoir pressure declines, secondary recovery methods may be employed. This often involves injecting water or gas back into the reservoir to increase the pressure and sweep more oil towards the production wells.

In some cases, tertiary or enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques are used. These can include injecting steam to heat the oil and reduce its viscosity, or using chemicals to help release the oil from the rock.

Cleaning it Up: Processing and Separation

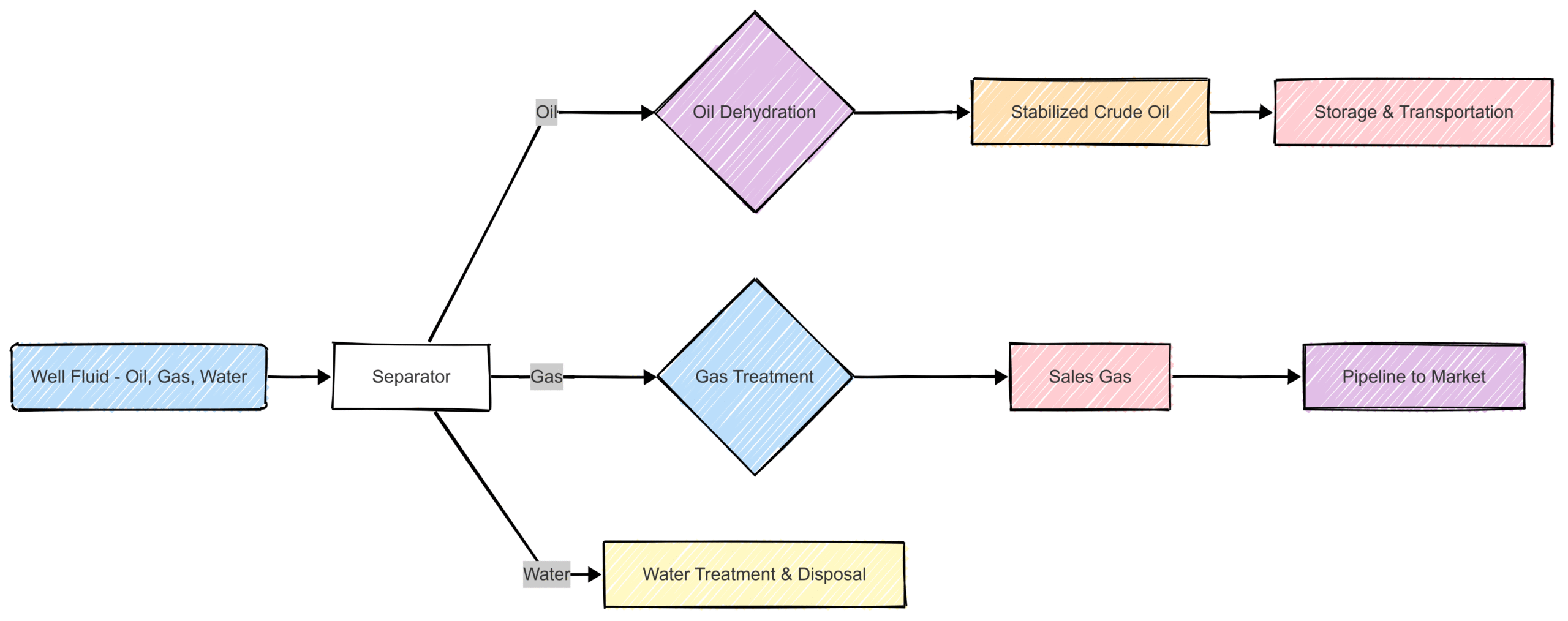

The fluids that come out of the well are a mixture of crude oil, natural gas, water, and sediment. Before the oil and gas can be sold, they must be separated and processed. This takes place at a central processing facility on the oilfield. The key steps include:

Separation: The mixture is passed through large vessels called separators, where the oil, gas, and water are separated based on their different densities.

Dehydration: Any remaining water is removed from the oil.

Gas Treatment: The natural gas is treated to remove impurities like water vapor and other gases.

Stabilization: The processed crude oil is stabilized to ensure it can be safely transported.

Getting it to Market: Transportation

Once processed, the oil and gas are ready to be transported to refineries and consumers. Onshore, this is typically done through a network of pipelines. Crude oil is also often transported by trucks or trains.

The Final Chapter: Decommissioning and Restoration

Every oilfield has a finite lifespan. When the production of oil and gas is no longer economically viable, the oilfield enters the decommissioning phase. This is the process of safely and responsibly closing the site and restoring the land to its original condition.

Plugging the Wells

The first and most critical step in decommissioning is to permanently plug the wells. This involves setting multiple cement plugs at various depths within the wellbore to ensure that there is no possibility of oil, gas, or water migrating to the surface or between different geological formations in the future.

Removing the Infrastructure

Once the wells are securely plugged, all surface facilities are dismantled and removed. This includes the drilling rigs, processing equipment, pipelines, and any buildings or structures on the site.

Restoring the Land

The final step is land restoration. The site is re-contoured to its original topography, and native vegetation is replanted. The goal is to return the land to a state that is as close as possible to its condition before the oilfield development began. This process is often monitored for several years to ensure the successful re-establishment of the local ecosystem.

Navigating the Landscape: Key Considerations in Onshore Oilfield Development

The development of an onshore oilfield is not just a technical endeavor; it is also a complex interplay of economic, environmental, and social factors.

The Economic Equation

The decision to develop an oilfield is ultimately an economic one. Oil companies must carefully weigh the significant upfront investment required for exploration, drilling, and infrastructure against the potential returns from the sale of oil and gas. The price of oil, the cost of technology, and government royalties all play a significant role in this calculation.

Environmental Stewardship

The oil and gas industry operates under stringent environmental regulations. Companies are required to conduct thorough environmental impact assessments, obtain numerous permits, and implement measures to protect air and water quality, minimize land disturbance, and protect wildlife. Modern oilfield development places a strong emphasis on sustainable practices and minimizing the environmental footprint.

Technological Advancements

The oil and gas industry is constantly evolving, driven by technological innovation. Advances in seismic imaging, drilling techniques, and data analytics are making it possible to find and produce oil and gas more efficiently and with a smaller environmental impact. Technologies like horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing have unlocked vast new resources in unconventional reservoirs, transforming the global energy landscape. The increasing use of digitalization and artificial intelligence is further optimizing operations and improving safety.

Conclusion: Powering the Present, Building the Future

Onshore oilfield development is a multifaceted and dynamic industry that plays a crucial role in meeting the world’s energy needs. From the initial search for hidden resources to the final act of restoring the land, it is a journey that combines cutting-edge technology, rigorous planning, and a deep understanding of the Earth’s geology.

As the world continues its transition towards a more diverse energy mix, the onshore oil and gas industry will continue to adapt and innovate, ensuring a reliable supply of energy while striving for greater environmental responsibility. Understanding the complete lifecycle of an onshore oilfield provides a valuable perspective on the complexities and challenges of powering our modern world.