Oil and Gas Upstream, Midstream, and Downstream Explained: A Complete Guide

The oil and gas industry is the engine of the modern world, a colossal network that powers our cars, heats our homes, and creates the building blocks for countless products we use every day. But how does a raw resource buried deep within the earth transform into the fuel in your tank or the plastic in your phone? The journey is a complex one, neatly divided into three core sectors: upstream, midstream, and downstream.

Understanding this value chain is crucial for anyone interested in energy, finance, or global economics. Each segment has its own unique risks, technologies, and economic drivers. This comprehensive guide will demystify these sectors, exploring the processes, players, and technologies that define them. We’ll take you on a journey from the initial discovery of a hydrocarbon reservoir to the final sale at the gas pump, complete with clear diagrams to illustrate each stage.

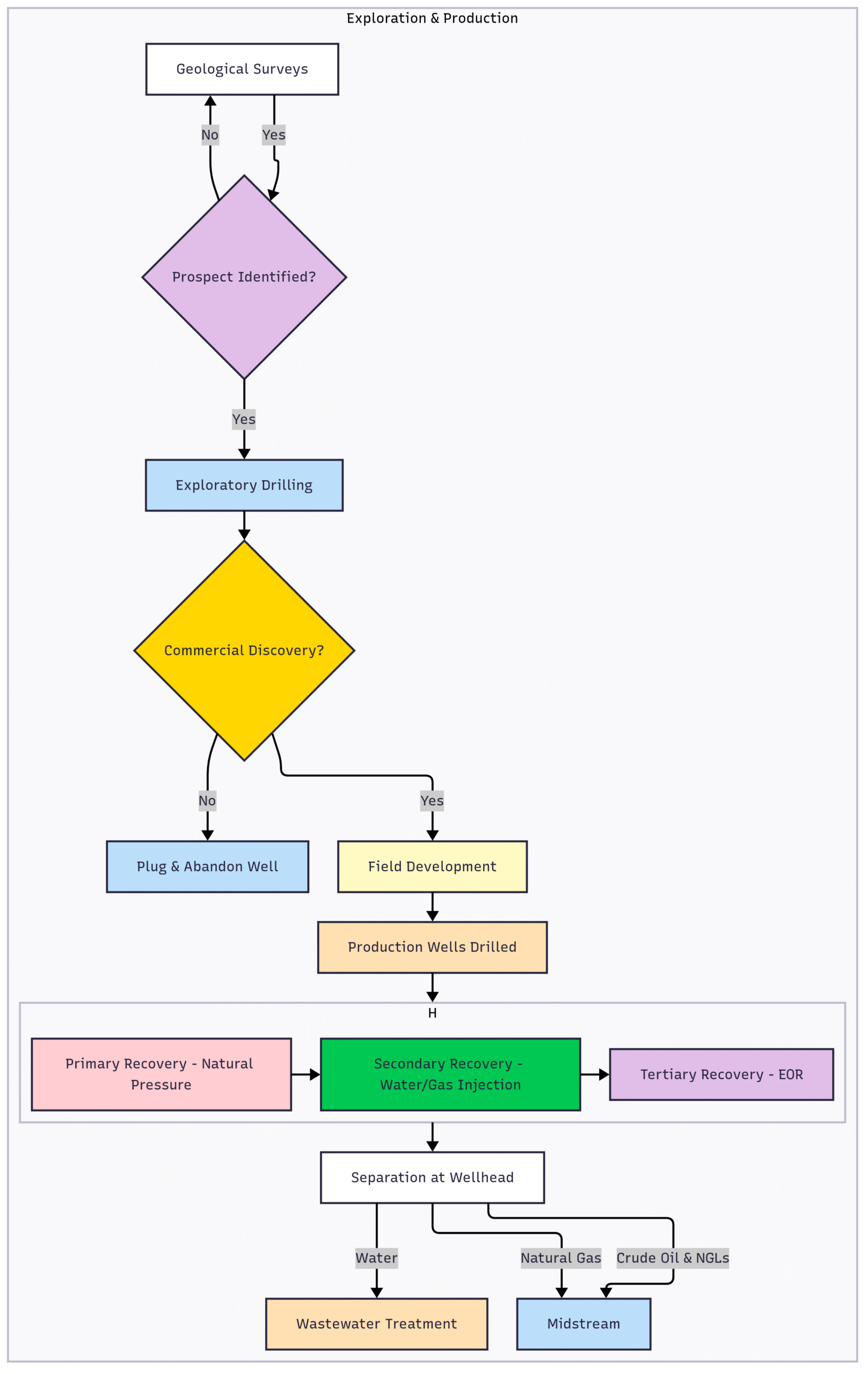

The Upstream Sector: Finding and Producing a Hidden Treasure

The upstream sector is where the oil and gas journey begins. It’s often called the Exploration and Production (E&P) sector because its sole focus is on finding underground or underwater crude oil and natural gas reservoirs, drilling exploratory wells, and subsequently operating the wells that recover and bring the raw materials to the surface. This is arguably the most high-risk, high-reward segment of the industry.

Imagine being a modern-day treasure hunter, but instead of a map with an “X,” you have sophisticated geological data and seismic imaging. E&P companies invest billions of dollars to locate and tap into these energy sources, often in some of the world’s most remote and challenging environments, from the scorching deserts of the Middle East to the icy waters of the Arctic.

Exploration: The Search for Black Gold

Before a single drill bit touches the ground, an immense amount of scientific work is done. Geologists and geophysicists are the detectives of the upstream world. Their primary goal is to identify sedimentary basins and specific geological formations (known as traps) where hydrocarbons are likely to have accumulated.

The key methods used in exploration include:

Seismic Surveys: This is the most common method. It involves generating shock waves—either with a specialized “thumper” truck on land or an air gun at sea—that travel deep into the earth. These waves bounce off different rock layers and are recorded by sensors called geophones or hydrophones. By analyzing the time it takes for the waves to return, geoscientists can create detailed 3D maps of the subsurface geology, revealing potential hydrocarbon-bearing structures.

Gravity and Magnetic Surveys: These surveys measure minute variations in the Earth’s gravitational and magnetic fields. Certain anomalies can indicate the presence of sedimentary basins where oil and gas might be trapped.

Exploratory Drilling: Once a promising location (a “prospect”) is identified, the only way to confirm the presence of oil or gas is to drill an exploratory well, often called a “wildcat well.” This is the moment of truth. Many exploratory wells turn up dry, making this a financially risky endeavor.

Production: Bringing Resources to the Surface

If an exploratory well strikes oil or gas in commercially viable quantities, the focus shifts from exploration to production. This phase involves developing the field to extract the hydrocarbons efficiently and safely over many years, or even decades. An oil or gas field is not like an underground lake; the hydrocarbons are trapped within the tiny pores of rocks like sandstone or shale.

Production involves several key stages:

Well Development: More wells, known as production or development wells, are drilled into the reservoir to maximize recovery.

Extraction: At first, the natural pressure within the reservoir is often enough to push the oil and gas to the surface. This is known as Primary Recovery. Over time, as this pressure depletes, Secondary Recovery techniques are employed, such as injecting water or gas back into the reservoir to increase pressure and “sweep” more oil toward the production wells.

Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR): In the final stages of a field’s life, Tertiary or Enhanced Oil Recovery methods may be used. These are more advanced and expensive techniques, such as injecting steam to heat the oil and reduce its viscosity, or using CO₂ or chemical floods to push out the remaining hydrocarbons.

Unconventional Production: The rise of hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) and horizontal drilling has revolutionized the industry. These technologies allow companies to unlock vast amounts of oil and gas from “tight” rock formations like shale, which were previously inaccessible. Fracking involves pumping a high-pressure mixture of water, sand, and chemicals into a well to create small fractures in the rock, allowing the trapped hydrocarbons to flow out.

Below is a diagram illustrating the key phases of the upstream sector.

Key players in the upstream sector range from supermajors (like ExxonMobil, Shell, and BP), which have integrated operations across all three sectors, to national oil companies (NOCs) (like Saudi Aramco and QatarEnergy), which are state-owned, and smaller independent E&P companies that focus exclusively on finding and producing hydrocarbons.

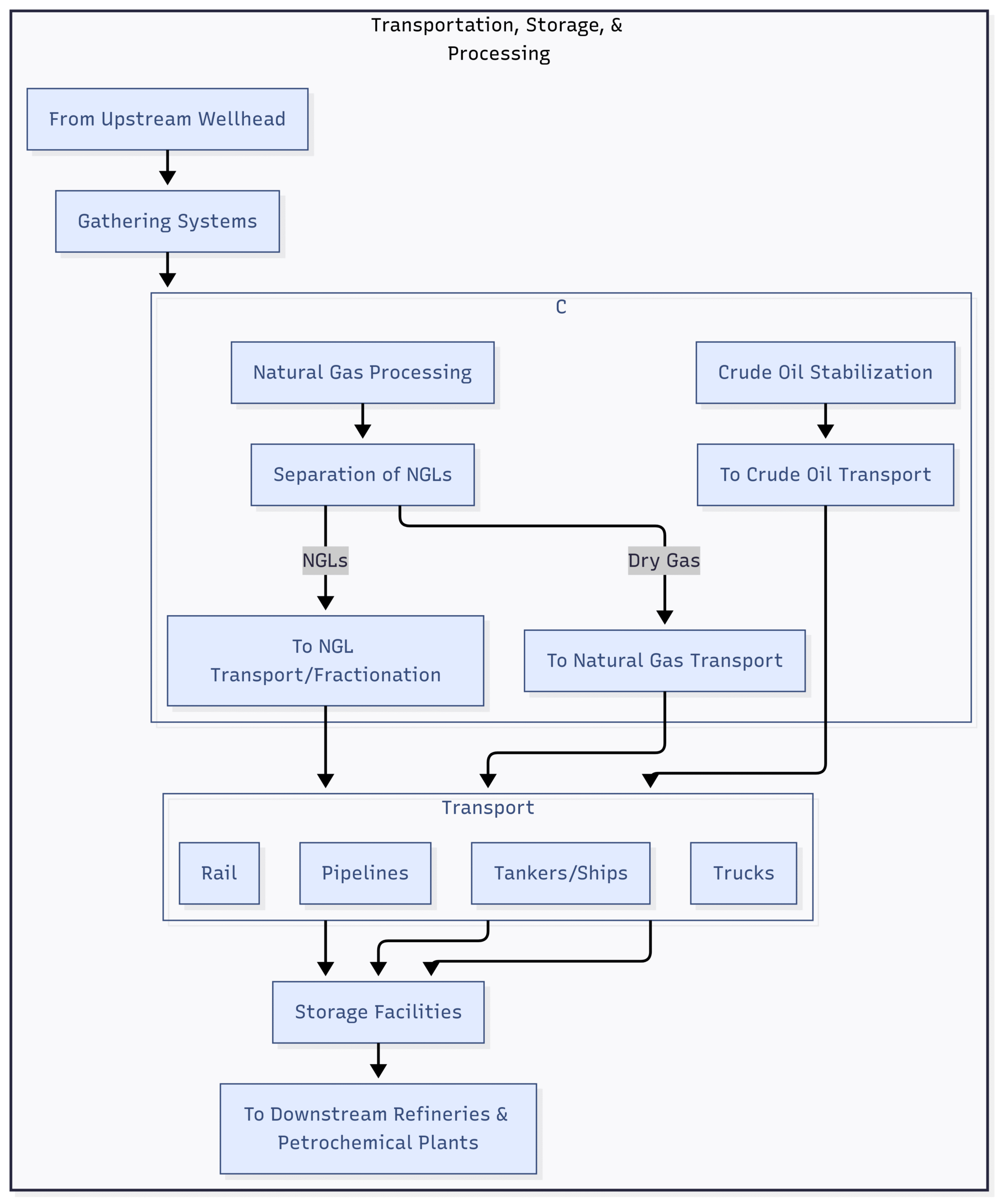

The Midstream Sector: The Energy Superhighway 🛣️

Once oil and gas are extracted from the ground, they must be transported, stored, and processed before they can be refined. This is the domain of the midstream sector. If upstream is about finding the treasure, midstream is about safely and efficiently moving that treasure to the factory. Midstream is the vital link connecting the remote production sites of the upstream with the population centers where the downstream sector operates.

The midstream sector is often characterized by long-term contracts and is generally less sensitive to commodity price fluctuations than the upstream sector. Its business model is more like a toll road or a storage facility—it earns fees for transporting and storing products for its customers.

Transportation: A Network of Arteries

Moving massive quantities of crude oil, natural gas, and natural gas liquids (NGLs) across vast distances is a logistical masterpiece. The primary modes of transportation are:

Pipelines: This is the most efficient, reliable, and cost-effective way to transport large volumes of oil and gas over land. An intricate network of pipelines crisscrosses continents, acting as the industry’s primary arteries. There are gathering pipelines that move raw product from the wellhead to processing facilities, and transmission pipelines that transport it over long distances to refineries or ports.

Tankers (Maritime): For cross-continental transport, there is no substitute for the mighty oil tanker. These massive ships, ranging from smaller vessels to Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCCs) that can hold over 2 million barrels of oil, are the workhorses of global energy trade. Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) is transported in specialized cryogenic carriers that keep the gas in its liquid state at -162°C (-260°F).

Rail and Truck: While less efficient for long hauls, rail cars and tanker trucks provide crucial flexibility. They are often used to transport oil from newer production areas that are not yet connected to major pipeline networks, or for delivering refined products to end-users in the downstream sector.

Storage and Processing

Midstream is not just about movement; it’s also about storage and initial processing.

Storage: Large storage facilities, often consisting of massive above-ground tanks grouped together in “tank farms,” are essential. They provide a buffer to help balance supply and demand, ensuring a steady flow of feedstock to refineries even if production is temporarily disrupted. Natural gas is typically stored in vast underground salt caverns or depleted reservoirs.

Natural Gas Processing: Raw natural gas that comes from the wellhead is not the same as the clean methane gas that reaches our homes. It’s a mixture of methane and various other hydrocarbons (NGLs like ethane, propane, and butane), as well as impurities like water, sulfur, and carbon dioxide. Midstream processing plants are responsible for separating this raw gas into its various components. The “dry” pipeline-quality natural gas is sent to consumers, while the valuable NGLs are separated and sold to the petrochemical industry.

Liquefaction and Regasification: To transport natural gas by ship, it must be converted into Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). This is done at a liquefaction plant, which cools the gas until it becomes a liquid, reducing its volume by 600 times. Upon arrival at its destination, the LNG is returned to its gaseous state at a regasification terminal before being fed into the local pipeline grid.

This diagram illustrates the flow of resources through the midstream sector.

Midstream companies often operate as master limited partnerships (MLPs) and provide stable, fee-based cash flows, making them attractive to income-focused investors. Major players include companies like Enterprise Products Partners, Kinder Morgan, and Enbridge.The Downstream Sector: From Raw Material to Everyday Products ⛽

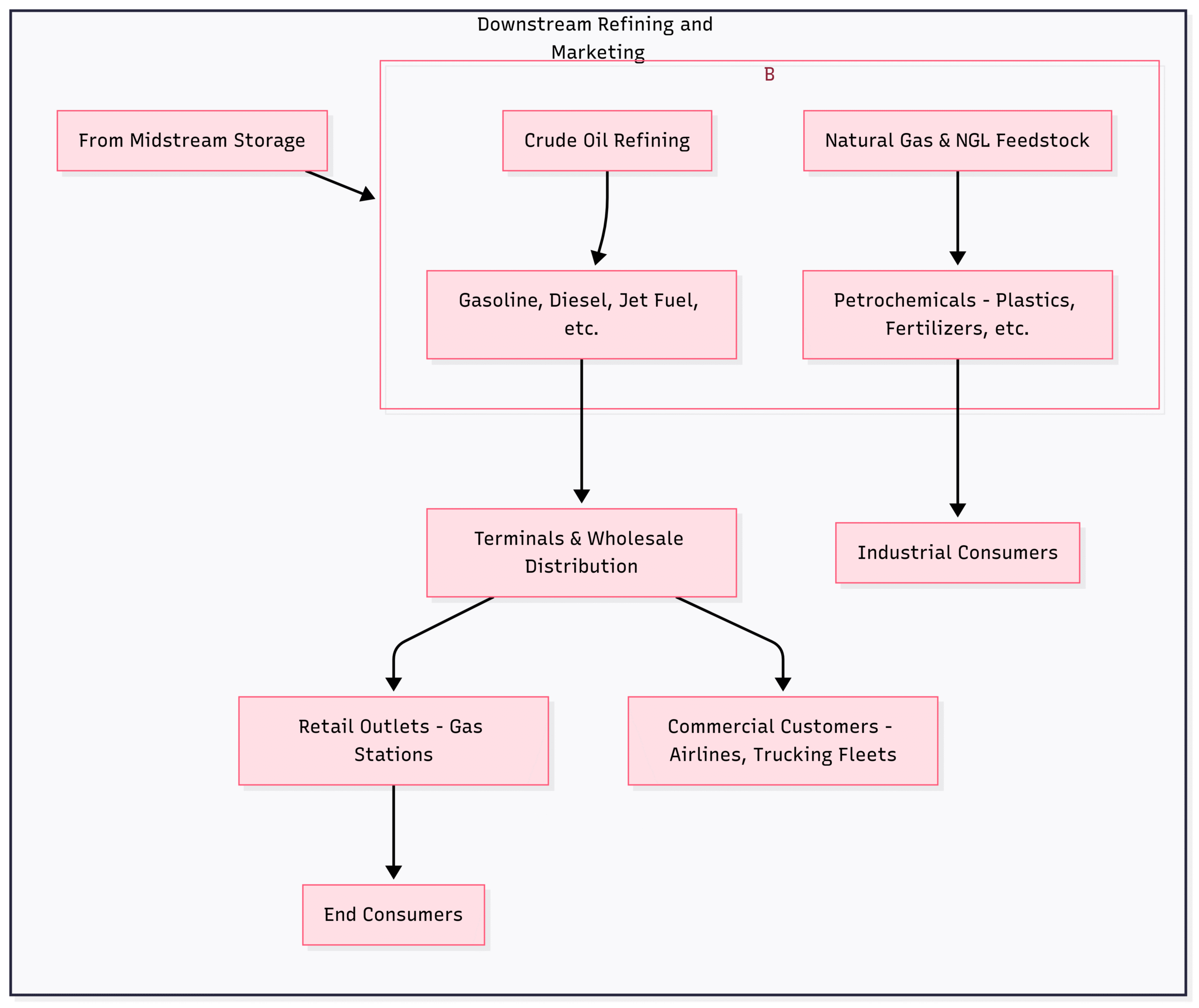

The final stage of the value chain is the downstream sector. This is the part of the industry that is most visible to the public. Downstream is all about refining crude oil, processing and purifying raw natural gas, and marketing and distributing the finished products to consumers, businesses, and industries. If upstream is the well and midstream is the highway, downstream is the factory, the warehouse, and the storefront.

The profitability of the downstream sector is heavily dependent on the “crack spread”—the price difference between a barrel of crude oil and the value of the refined products produced from it.

Refining: The Industrial Alchemy

A refinery is a massive, complex industrial facility that transforms crude oil into a wide range of valuable petroleum products. The process is one of modern alchemy, where the thick, dark raw material is heated, separated, and converted into lighter, more useful substances.

The primary process is distillation.

Atmospheric Distillation: Crude oil is heated to high temperatures (around 400°C or 752°F) and fed into a tall distillation column. As the hot vapor rises, it cools and condenses at different levels.

Lighter products with lower boiling points (like butane and gasoline) rise higher up the column before condensing.

Heavier products with higher boiling points (like kerosene, diesel, and lubricating oils) condense at lower levels.

The very heaviest material, called residuum, remains at the bottom.

Further Processing: The residuum from the distillation column is often sent to a second vacuum distillation unit to be further separated. Other sophisticated processes are then used to “crack” heavy hydrocarbon molecules into lighter, more valuable ones (like gasoline) and to treat and purify the products to meet strict quality and environmental standards. These processes include cracking, reforming, and hydrotreating.

Petrochemicals: The Building Blocks of Modern Life

A significant portion of the hydrocarbons from both oil and gas (especially NGLs like ethane and propane) are used as feedstock for the petrochemical industry. Petrochemical plants use these raw materials to create the fundamental building blocks for an astonishing array of products, including:

Plastics (polyethylene, polypropylene, PVC)

Synthetic rubber and synthetic fibers (nylon, polyester)

Fertilizers, pesticides, and detergents

Solvents, adhesives, and paints

Without the downstream sector, we wouldn’t have smartphones, life-saving medical devices, lightweight car parts, or modern clothing.

Marketing and Distribution

The final step is getting these finished products to the end-user. This is the “marketing” or “retail” part of the downstream sector. It includes:

Wholesale Operations: Selling large quantities of fuel and other products to distributors, utility companies, and other large-scale consumers.

Retail Operations: This is the most familiar face of the industry—the branded gas stations (like Shell, Chevron, or TotalEnergies) where consumers fill up their cars. These retail outlets are the final point of sale in the long journey from the reservoir.

Distribution Networks: A complex network of terminals, pipelines, and trucks is used to deliver products like gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel from the refinery to airports, businesses, and retail stations.

Here is a diagram summarizing the key components of the downstream sector.

Conclusion: A Symbiotic Chain

The upstream, midstream, and downstream sectors of the oil and gas industry form a deeply interconnected and symbiotic value chain. Each segment relies on the others to function. Without successful exploration and production (upstream), there would be nothing to transport or refine. Without efficient transportation and storage (midstream), the resources would be stranded. And without refining and marketing (downstream), the raw materials would have no end-use.

From the high-stakes gamble of a wildcat well to the mundane act of filling a car with gasoline, this three-part journey is what fuels our global economy. By understanding the distinct roles and challenges of the upstream, midstream, and downstream sectors, one can gain a much deeper appreciation for the complexity and importance of the energy that shapes our world. What part of this energy journey do you find most fascinating? Let us know in the comments below!

Other related topics

- Oil & Gas Upstream, Midstream, & Downstream: The Complete Guide (2025)

- What Are Upstream, Midstream, and Downstream? An Oil & Gas Explainer

- The Oil & Gas Value Chain Explained: From Wellhead to Gas Pump

- Upstream vs. Midstream vs. Downstream: Understanding the 3 Oil & Gas Sectors

- A Deep Dive into Oil and Gas: Upstream, Midstream, and Downstream

- Decoding the Energy Sector: A Guide to Upstream, Midstream, & Downstream

- From Exploration to Your Car: The Journey Through Oil & Gas Sectors

- How the Oil & Gas Industry Works: Upstream, Midstream & Downstream

- An Analysis of the Upstream, Midstream, and Downstream Operations

- The Pillars of Oil & Gas: Explaining Upstream, Midstream, and Downstream

Thanks for finally writing about > Upstream vs. Midstream

vs. Downstream: Understanding the 3 Oil & Gas Sectors – InstruNexus < Liked it!