How to Conduct a Functional Safety Audit: An IEC 61511 Perspective

In the high-stakes world of industrial automation, ensuring the safety of your processes is not just a best practice; it’s a critical necessity. For industries dealing with hazardous materials and processes, the Safety Instrumented System (SIS) is the last line of defense against catastrophic events. The international standard IEC 61511 provides a framework for the entire lifecycle of an SIS, from initial conception to decommissioning. But how do you ensure your organization is consistently adhering to these rigorous requirements? The answer lies in a robust Functional Safety Audit program.

This comprehensive guide will walk you through the process of conducting a Functional Safety Audit from the perspective of IEC 61511. We will explore the what, why, and how of these essential evaluations, complete with block diagrams to illustrate the key stages. At over 2000 words, this article will serve as a detailed roadmap for anyone involved in ensuring the functional safety of their operations.

Understanding the Functional Safety Audit

A Functional Safety Audit, in the context of IEC 61511, is a systematic and independent examination to determine whether the procedures and practices in place for managing functional safety are being followed. It is a proactive measure designed to identify and rectify non-conformities before they can compromise the integrity of your safety systems.

It is crucial to distinguish a Functional Safety Audit from a Functional Safety Assessment (FSA). While often used interchangeably, they have distinct meanings within IEC 61511:

Functional Safety Audit: Focuses on the management system for functional safety. It checks if you have the right procedures, if they are adequate, and if they are being followed. Think of it as auditing the “paperwork” and the processes.

Functional Safety Assessment (FSA): A more in-depth investigation that judges the functional safety achieved by the SIS. It’s a technical review to confirm that the safety functions will meet their required Safety Integrity Level (SIL).

In essence, an audit verifies that you are “doing the right things,” while an assessment confirms that you have “achieved the right outcome.” This blog will focus on the audit process, which is a fundamental prerequisite for a successful FSA.

Why are Functional Safety Audits so Important?

Conducting regular Functional Safety Audits offers a multitude of benefits:

Compliance: Demonstrates adherence to the requirements of IEC 61511 and other relevant regulations.

Risk Reduction: Proactively identifies weaknesses in your functional safety management system, reducing the likelihood of SIS failures.

Improved Performance: Drives consistency and continuous improvement in your safety-related practices.

Increased Confidence: Provides assurance to stakeholders, including management, employees, and regulatory bodies, that functional safety is being effectively managed.

Cost Savings: Identifying and correcting procedural deficiencies early on is far less expensive than dealing with the consequences of a safety incident.

The Functional Safety Audit Process: A Four-Phase Approach

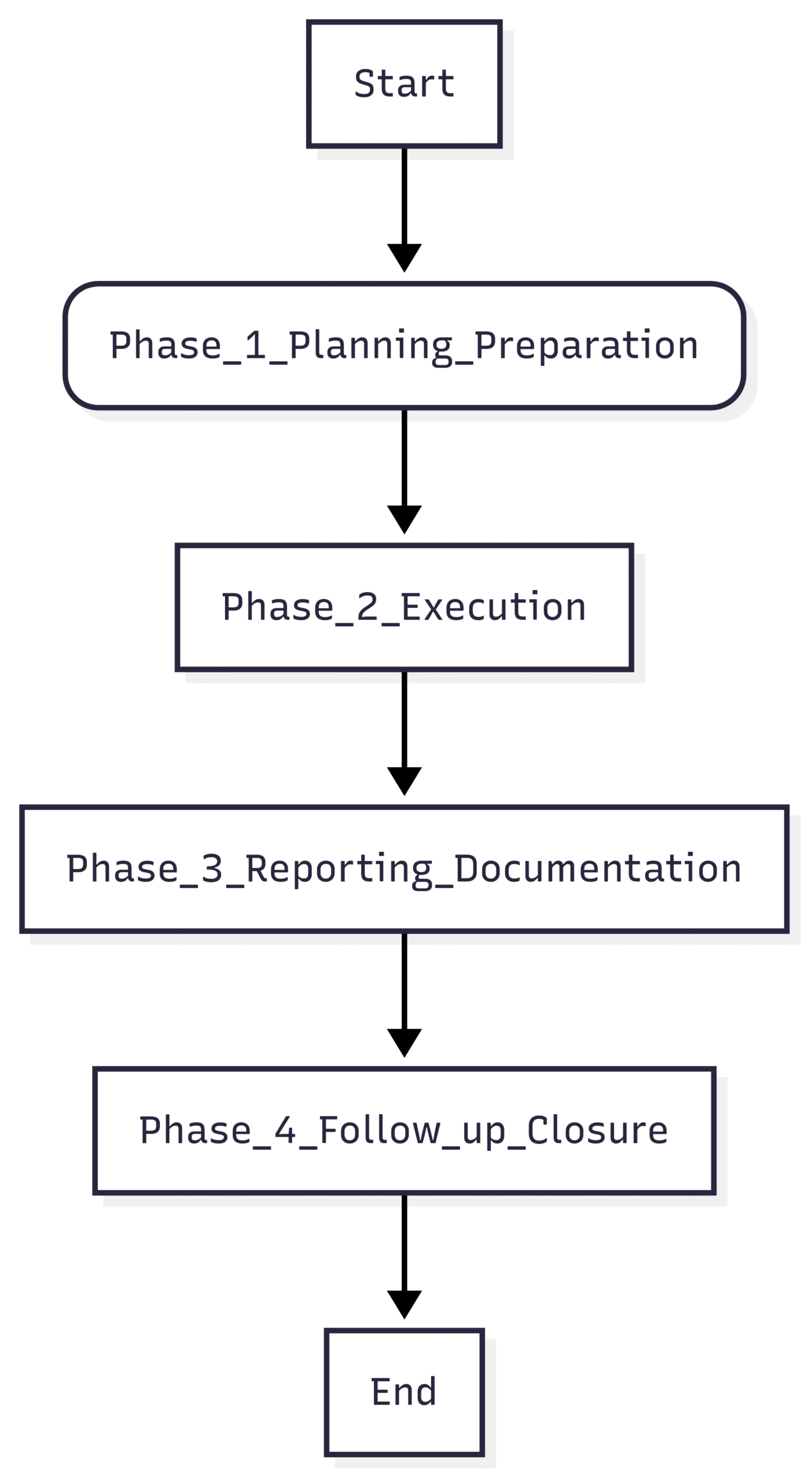

A well-structured Functional Safety Audit can be broken down into four distinct phases:

Planning and Preparation: The foundation for a successful audit.

Execution: The on-the-ground (or in-the-office) investigation.

Reporting and Documentation: Communicating the audit findings.

Follow-up and Closure: Ensuring corrective actions are implemented and effective.

Let’s delve into each of these phases in detail.

Phase 1: Planning and Preparation

Thorough planning is the most critical phase of the audit process. Rushing into an audit without adequate preparation is a recipe for an inefficient and ineffective evaluation.

High-Level Block Diagram of the Functional Safety Audit Process

Key Activities in the Planning Phase:

Define the Audit Scope and Objectives:

Scope: What aspects of the functional safety management system will be audited? Will it cover the entire safety lifecycle, or specific phases like design, operation, or maintenance? Will it focus on a particular plant area or a specific project?

Objectives: What do you aim to achieve with the audit? Examples include:

To verify compliance with the company’s Functional Safety Management Plan.

To assess the competency of personnel involved in safety lifecycle activities.

To identify opportunities for improvement in the proof testing procedures.

Select the Audit Team:

Lead Auditor: An individual with extensive experience in both auditing techniques and functional safety. They will be responsible for managing the audit team and the overall audit process.

Team Members: A multidisciplinary team with expertise in relevant areas such as process engineering, instrumentation and control, and operations.

Independence: The audit team must be independent of the activities being audited to ensure objectivity. This may necessitate bringing in third-party experts.

Competence: All team members must be competent in the principles of functional safety and the requirements of IEC 61511.

Develop the Audit Plan: This is the roadmap for the audit and should include:

The audit scope, objectives, and criteria.

The schedule and duration of the audit.

The members of the audit team and their roles.

The departments and personnel to be interviewed.

A list of required documents to be reviewed.

The logistics of the audit (e.g., travel, site access).

Prepare the Audit Checklist: The checklist is a vital tool for ensuring a systematic and comprehensive audit. It should be based on the requirements of IEC 61511 and the organization’s own functional safety procedures. The checklist should be structured to cover all aspects of the audit scope and should prompt the auditor to gather objective evidence. A good checklist will include open-ended questions to encourage discussion rather than simple “yes/no” answers.

Initial Document Review: Before the on-site audit begins, the audit team should review key documents such as:

The Functional Safety Management Plan.

Safety Requirements Specifications (SRS).

Hazard and Risk Analysis (HAZOP) reports.

SIL verification calculations.

Proof testing procedures and records.

Management of Change (MOC) procedures.

Competency records of personnel.

Phase 2: Execution

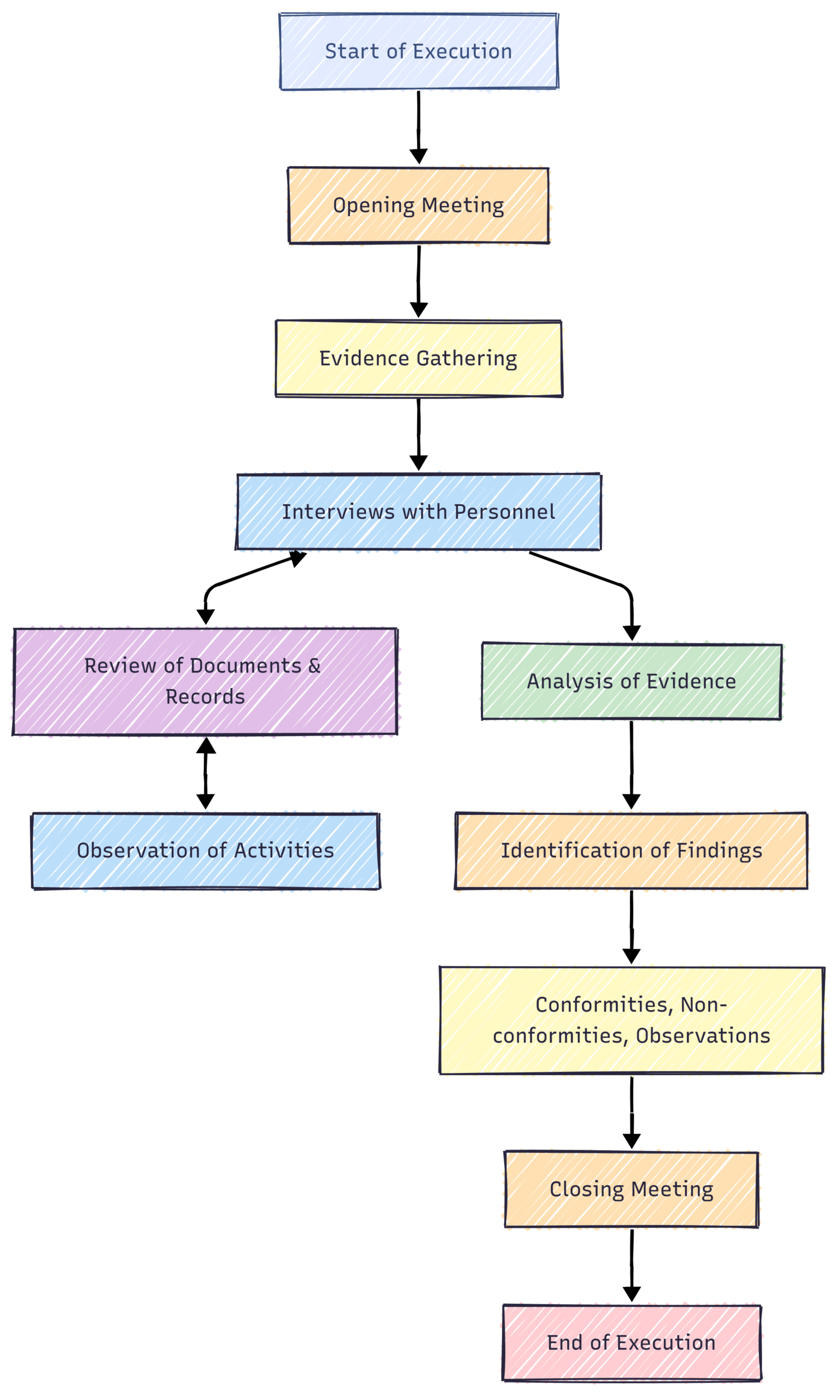

This is the fact-finding phase where the audit team gathers evidence to assess compliance with the audit criteria.

Detailed Block Diagram of the Audit Execution Phase

Key Activities in the Execution Phase:

Opening Meeting: The audit begins with a formal opening meeting with the management of the audited organization. The purpose of this meeting is to:

Introduce the audit team.

Confirm the audit plan and scope.

Explain the audit process and methodology.

Establish communication channels.

Answer any questions from the auditees.

Evidence Gathering: This is the core of the audit. The audit team will use a combination of techniques to gather objective evidence:

Interviews with Personnel: This is a crucial method for understanding how work is actually performed. Auditors should interview a cross-section of personnel, from engineers and operators to maintenance technicians and managers. Questions should be open-ended and designed to verify their understanding and application of functional safety procedures.

Review of Documents and Records: The auditors will delve deeper into the documentation, comparing the procedures with the actual records of activities. This includes reviewing completed proof test records, maintenance logs, and training certificates.

Observation of Activities: Where possible, auditors should observe safety-related activities being performed, such as proof testing of a safety instrumented function (SIF) or a management of change meeting. This provides direct evidence of compliance (or non-compliance).

Analysis of Evidence: As evidence is gathered, the audit team must continuously analyze it against the audit criteria (IEC 61511 and internal procedures). This involves looking for patterns, inconsistencies, and gaps.

Identification of Findings: Based on the analysis of evidence, the audit team will identify findings, which are typically categorized as:

Conformity: An area where the requirements are being met.

Non-conformity (NC): A failure to meet a requirement. Non-conformities can be further classified as major or minor depending on their potential impact on safety.

Observation (or Opportunity for Improvement – OFI): An area that is currently in compliance but could be improved to enhance robustness or efficiency.

Closing Meeting: At the conclusion of the on-site audit, a closing meeting is held with the auditees. The purpose of this meeting is to:

Thank the auditees for their cooperation.

Present a summary of the audit findings, including all non-conformities.

Ensure that the auditees understand the findings.

Discuss the next steps in the audit process, including the timeline for the audit report.

Phase 3: Reporting and Documentation

The audit report is the formal record of the audit and its findings. It should be clear, concise, and accurate.

Key Elements of the Audit Report:

Executive Summary: A high-level overview of the audit, including the key findings and conclusions.

Audit Details: The scope, objectives, dates, and team members.

Summary of the Audit Process: A brief description of how the audit was conducted.

Detailed Findings: A comprehensive list of all non-conformities and observations, supported by objective evidence. Each finding should clearly state the requirement, the evidence of non-compliance, and the potential consequence.

Positive Findings: It is also good practice to highlight areas of strong performance and best practices.

Conclusion: An overall assessment of the effectiveness of the functional safety management system.

Recommendations: While the primary role of the auditor is to identify non-conformities, they may also provide recommendations for corrective actions. However, the responsibility for developing and implementing these actions lies with the auditee.

Phase 4: Follow-up and Closure

An audit is only effective if it leads to improvement. The follow-up phase is crucial for ensuring that corrective actions are implemented and that they effectively address the root causes of the non-conformities.

Key Activities in the Follow-up Phase:

Corrective Action Plan (CAP): The audited organization is responsible for developing a CAP that addresses each non-conformity. The CAP should include:

The root cause analysis of the non-conformity.

The proposed corrective action.

The person responsible for implementing the action.

The deadline for completion.

Review and Approval of the CAP: The lead auditor should review the CAP to ensure that the proposed actions are adequate to address the non-conformities.

Verification of Corrective Actions: Once the corrective actions have been implemented, their effectiveness must be verified. This may involve a follow-up visit by the audit team or the submission of evidence by the audited organization.

Audit Closure: The audit is formally closed once all corrective actions have been verified as complete and effective.

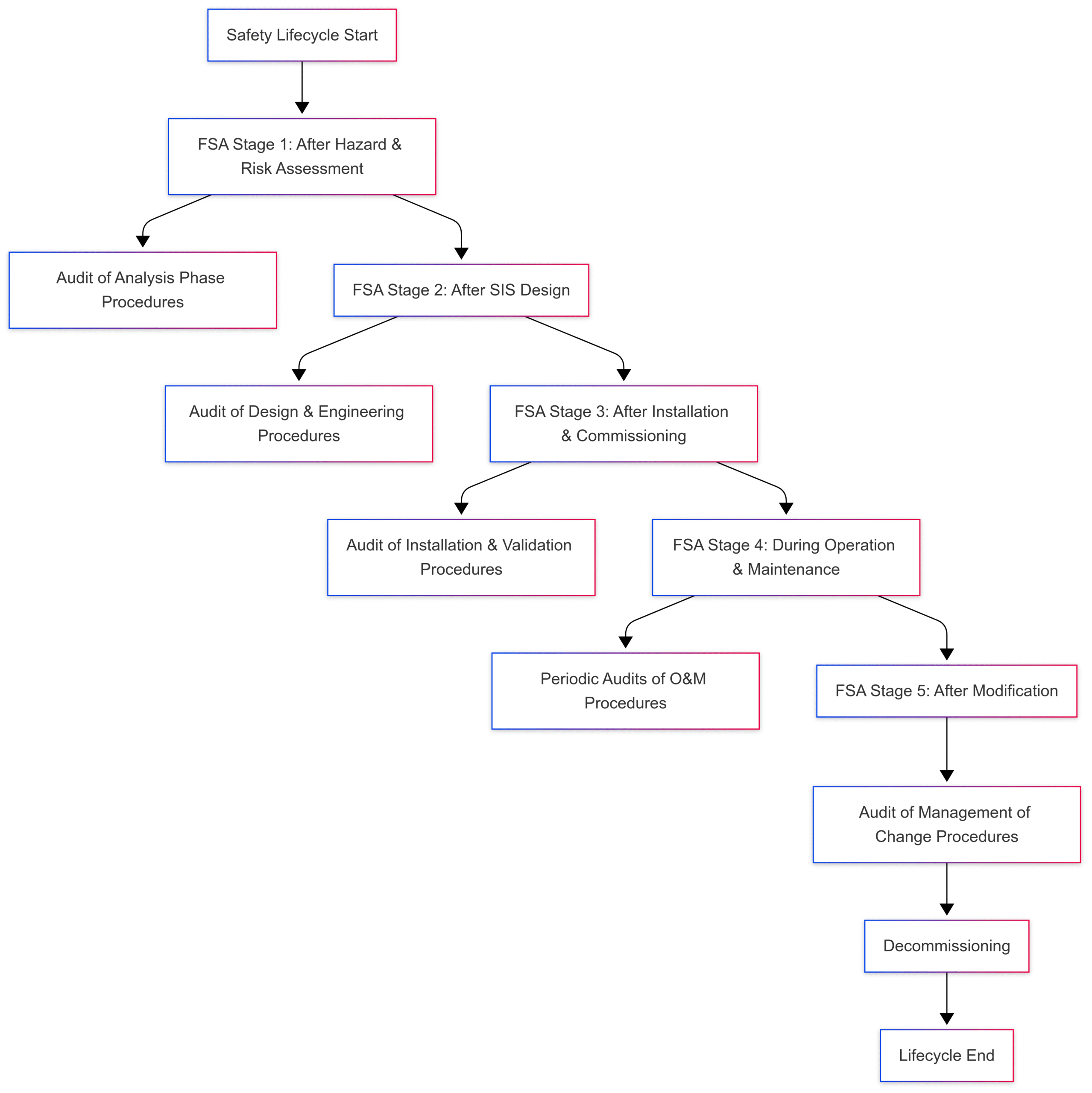

The Audit and the IEC 61511 Safety Lifecycle

Functional Safety Audits should not be one-off events. They should be integrated into the overall safety lifecycle. IEC 61511 defines five stages for Functional Safety Assessments (FSAs), and audits can be conducted in conjunction with these stages to ensure the underlying management system is robust.

Block Diagram: Relationship between Audits and FSA Stages

FSA Stage 1: An audit at this stage would focus on the procedures for conducting hazard and risk assessments, allocating safety functions, and developing the SRS.

FSA Stage 2: The audit would scrutinize the design and engineering procedures, including SIL verification, software design, and hardware selection.

FSA Stage 3: This audit would examine the procedures for installation, commissioning, and validation of the SIS.

FSA Stage 4: Periodic audits during the operational phase are critical. They would cover proof testing, maintenance, management of change, and incident investigation procedures.

FSA Stage 5: When modifications are made to the SIS, an audit should be conducted to ensure that the management of change procedures are being followed correctly.

Conclusion: Fostering a Culture of Safety

Conducting a Functional Safety Audit in accordance with IEC 61511 is a rigorous but essential undertaking. It is far more than a simple box-ticking exercise. A well-executed audit program provides a powerful mechanism for driving continuous improvement and fostering a culture where safety is ingrained in every aspect of your operations.

By embracing a systematic, four-phase approach to auditing – Plan, Execute, Report, and Follow-up – organizations can gain invaluable insights into the health of their functional safety management system. The block diagrams provided in this guide offer a visual framework for understanding this process.

Ultimately, the goal of a Functional Safety Audit is not to find fault, but to find opportunities for improvement. By proactively identifying and addressing weaknesses, you can significantly enhance the reliability of your safety instrumented systems and, most importantly, protect your people, your assets, and the environment. In the world of functional safety, vigilance is not just a virtue; it is the cornerstone of a safe and sustainable future.