Orifice Plate vs. Restriction Orifice

A Masterclass in Fluid Dynamics, Pressure Control, and Flow Measurement.

Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction to Passive Flow Devices

- 2. The Fluid Mechanics: Bernoulli and Continuity

- 3. The Orifice Plate (FE): The Measurement Standard

- 4. The Restriction Orifice (RO): The Pressure Killer

- 5. Design and Construction Variances

- 6. Critical Comparison: FE vs. RO

- 7. Advanced Dynamics: Cavitation and Choked Flow

- 8. Industrial Applications

- 9. Standards, Installation, and Maintenance

- 10. Conclusion

1. Introduction to Passive Flow Devices

In the intricate world of process engineering, piping design, and instrumentation, the management of fluid flow is paramount. Among the myriad of complex valves, digital sensors, and automated control systems, two remarkably simple yet vital passive devices stand out: the Orifice Plate and the Restriction Orifice (RO). At first glance, these two components appear nearly identical—often just a metal plate with a hole in it—clamped between two flanges. However, their purposes, design criteria, and operational physics are distinct.

Understanding the nuance between an Orifice Plate (often designated as FE for Flow Element) and a Restriction Orifice (RO) is not merely a matter of semantics. It is a critical engineering competency that impacts plant safety, process efficiency, and measurement accuracy. While one is designed to measure the heartbeat of the plant (flow rate) by inducing a temporary disturbance, the other is designed to absorb excess energy, ensuring downstream equipment does not suffer from over-pressure or to limit flow rates during fault conditions.

This comprehensive guide explores the depths of these two devices, moving beyond simple definitions into the physics of pressure recovery, beta ratios, discharge coefficients, and the practical realities of installation in high-pressure petrochemical, power generation, and water treatment facilities.

2. The Fluid Mechanics: Bernoulli and Continuity

To appreciate the function of orifice plates and restriction orifices, we must first ground our understanding in the fundamental laws of fluid mechanics. Both devices operate on the principle of flow obstruction. By reducing the cross-sectional area through which a fluid flows, they induce changes in velocity and pressure.

The Continuity Equation

Q = A × V

Where Q is the volumetric flow rate, A is the cross-sectional area, and V is the fluid velocity. As the fluid passes from the pipe into the smaller bore of the orifice, the area (A) decreases. For the mass flow to remain constant (assuming incompressible flow), the velocity (V) must increase drastically.

Bernoulli’s Principle and Pressure Drop

Bernoulli’s principle states that within a flowing fluid, an increase in velocity occurs simultaneously with a decrease in static pressure. When the fluid accelerates through the bore of the orifice plate, its kinetic energy increases, and its potential energy (pressure) decreases.

The Vena Contracta: As fluid passes through the orifice, it doesn't immediately expand to fill the pipe. It converges to a minimum cross-section downstream of the plate, known as the vena contracta. This is the point of maximum velocity and minimum pressure.

Permanent Pressure Loss (PPL): Downstream of the vena contracta, the fluid expands and slows down. According to Bernoulli, pressure should recover. However, due to turbulence, friction, and eddy currents generated by the abrupt expansion, not all pressure is recovered. The energy lost to heat and sound results in a Permanent Pressure Loss. This concept is the divergence point for our two devices:

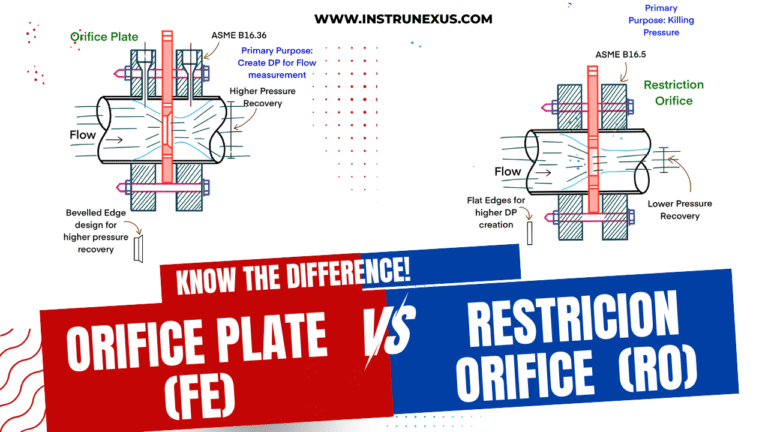

- Orifice Plates are designed to maximize pressure recovery (minimize PPL) to save energy, although they still introduce some loss.

- Restriction Orifices are designed to maximize Permanent Pressure Loss to dissipate energy.

3. The Orifice Plate (FE): The Measurement Standard

The Orifice Plate, typically denoted on P&IDs (Piping and Instrumentation Diagrams) as an FE (Flow Element), is a primary sensing element used for flow metering. It works in conjunction with a Differential Pressure (DP) Transmitter.

Principle of Operation

The FE creates a restriction to generate a differential pressure (Delta P). The relationship between the flow rate and the square root of the differential pressure is well established. The DP transmitter measures the pressure upstream (High side) and downstream (Low side).

Equation: Q = C x sqrt{Delta P}

Where Q is flow, Delta P is differential pressure, and C is a constant derived from the beta ratio, pipe diameter, and fluid properties.

Types of Orifice Plates

- Concentric Orifice: The most common type. The bore is in the exact center. Used for clean liquids, gases, and steam. The bevel is typically on the downstream side to minimize edge thickness effects.

- Eccentric Orifice: The bore is offset from the center, typically tangent to the bottom (for gas with liquids) or top (for liquids with gas) of the pipe. This prevents damming of solids or condensates.

- Segmental Orifice: The bore is a segment of a circle (like a semi-circle). Primarily used for slurry services or fluids with high suspended solids.

- Quadrant Edge: Used for highly viscous fluids (low Reynolds numbers) where the sharp edge of a standard plate would cause measurement errors.

Key Characteristic: Thin Plate

Measurement orifice plates are typically thin (e.g., 3mm to 6mm) to ensure a "sharp edge" facing the flow. A sharp edge is crucial for a predictable discharge coefficient. If the edge becomes rounded due to erosion, the flow reading will drift lower than the actual flow, creating a "negative bias."

4. The Restriction Orifice (RO): The Pressure Killer

While the FE is a sensor, the Restriction Orifice (RO) is a final control element, albeit a passive one. Its primary function is to remove energy from the process stream in a controlled manner.

Primary Functions of an RO

- Pressure Reduction: Reducing the pressure of a fluid from a high-pressure main header to a low-pressure distribution branch.

- Flow Limitation: Limiting the maximum flow rate that can pass through a line, regardless of how low the downstream pressure drops (choked flow condition). This is vital for safety, preventing a pipe rupture downstream from draining a vessel too quickly.

- Noise and Vibration Control: By staging pressure drops, ROs can prevent the massive noise associated with control valves taking a large drop.

Design: The Multi-Stage RO

Unlike the simple thin plate of a flow element, a Restriction Orifice often needs to handle massive pressure drops (e.g., dropping 100 bar gas to 5 bar). A single plate would result in extreme turbulence, noise, and cavitation.

Engineers often design Multi-Hole or Multi-Stage Restriction Orifice assemblies.

- Multi-Hole: Breaking one large jet into many small jets shifts the noise frequency higher (often outside human hearing range) and promotes faster energy dissipation.

- Multi-Stage: A spool piece containing several plates in series. Each plate takes a fraction of the total pressure drop, preventing cavitation and keeping velocities within limits.

Thickness matters

ROs are generally thicker than FEs. While an FE might be 3mm thick, an RO subject to a 50 bar drop might be 15mm or 20mm thick to prevent buckling under the differential force. The bore is often cylindrical (not beveled) to encourage friction and pressure loss.

5. Design and Construction Variances

The physical construction of these devices varies significantly based on their intended service.

Material Selection

Stainless Steel (304/316): The baseline for standard water, air, and hydrocarbon service.

Monel / Hastelloy: Used for corrosive environments, such as sour gas (H2S) or acids.

Stellite Overlay: For ROs in high-pressure steam or abrasive service, the bore may be hardened with Stellite to prevent erosion. Erosion in an RO changes the flow restriction capability, potentially compromising safety.

Mounting Styles

- Paddle Type: The most common. The plate has a handle (paddle) that extends outside the flange bolts, containing the tag number and bore info.

- Universal Type: A plate without a handle, designed to fit inside a specialized "Orifice Fitting" (like a Senior or Junior Daniels fitting) which allows removal under pressure.

- Spool Type: Used for multi-stage ROs. The plates are welded inside a pipe spool.

Flange and Tapping Requirements

The hardware required to install these devices differs significantly due to the requirement for signal transmission.

Orifice Plate (FE)

Requires Special "Orifice Flanges" (ASME B16.36)

To accurately measure flow, pressure must be tapped at precise locations relative to the plate face. Standard flanges block this access.

- Corner Tapping: Essential for high accuracy or small bore lines (ISO 5167). The flange is machined with a specific annular chamber or hole to measure pressure immediately at the corner of the plate.

- Flange Taps: Holes drilled radially through the flange rim (typically 1 inch from the plate face).

- Jack Screws: These flanges include extra "Jack Bolts" to spread the flanges apart, allowing the safe removal of the delicate sharp-edged plate.

Restriction Orifice (RO)

Uses Standard Piping Flanges (ASME B16.5)

Since the RO is used for energy dissipation rather than precision measurement, it does not require integrated tapping points.

- No Special Flanges: The RO is simply sandwiched between standard weld-neck or slip-on flanges.

- No Tapping: If pressure verification is required, it is done via standard threadolets on the pipe wall upstream or downstream, as the exact distance from the plate is less critical.

- Simplicity: It does not require jack screws or complex machining.

Drain and Vent Holes

In single-phase flows, there is often a risk of a secondary phase accumulating against the dam created by the orifice plate. This accumulation can lead to measurement errors in FEs or water hammer and corrosion in ROs. To mitigate this, small bypass holes are drilled into the non-bored section of the plate.

Orientation Rules

- Vent Hole (Liquid Service): Drilled at the very top of the plate (12 o'clock position). Allows trapped gas bubbles to pass downstream rather than building up and affecting the hydraulic profile.

- Drain Hole (Gas Service): Drilled at the very bottom of the plate (6 o'clock position). Allows condensed liquid (condensate) to drain, preventing "damming" which changes the effective pipe area.

Differences in Application:

The size of the drain/vent hole is strictly controlled (typically limited to a small percentage of the orifice bore). Because flow passing through this hole is "unmetered," it introduces a measurement error. Advanced flow calculations (ISO 5167) include factors to correct for this bypass flow, but the hole must remain small to maintain accuracy.

The primary concern here is mechanical integrity rather than measurement precision. Drain holes are absolutely critical in steam or wet gas service. Without them, condensate builds up behind the RO plate. This liquid can eventually be picked up by the high-velocity gas stream as a "slug," causing massive impact damage (Water Hammer) to downstream piping and supports.

6. Critical Comparison: FE vs. RO

The following table summarizes the distinct differences between the two devices.

| Feature | Orifice Plate (FE) | Restriction Orifice (RO) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Flow Measurement (creating a readable $\Delta P$) | Pressure Drop (Energy Dissipation) or Flow Limitation |

| Pressure Profile | Designed for High Pressure Recovery (Low Permanent Loss) | Designed for High Permanent Pressure Loss |

| Bore Edge | Sharp, Square Edge (Critical for accuracy) | Often Cylindrical, sometimes thick bore, not necessarily sharp |

| Plate Thickness | Thin (Standardized, e.g., 1/8") | Thick (Calculated based on bending moment of $\Delta P$) |

| Beta Ratio ($\beta = d/D$) | Typically 0.2 to 0.7 (optimized for linearity) | Can be very small (< 0.1) to achieve high restriction |

| Flow Condition | Usually Sub-sonic | Often Sonic (Choked) Flow in gas applications |

| Standard | ISO 5167, AGA 3, ASME MFC-3M | R.W. Miller, ISO 5167 (for sizing), but mainly custom engineering |

7. Advanced Dynamics: Cavitation and Choked Flow

One of the most dangerous aspects of orifice design is managing phase changes.

Liquid Service: Cavitation & Flashing

In liquid service, if the pressure at the vena contracta drops below the fluid's Vapor Pressure, bubbles form (flashing). When the pressure recovers downstream, these bubbles collapse with immense force. This is Cavitation.

Orifice Plates: Cavitation causes noisy measurement and destroys the sharp edge of the plate, ruining accuracy.

Restriction Orifices: Because ROs are designed for large pressure drops, they are highly prone to cavitation. To mitigate this, engineers use Multi-Stage ROs. By dropping pressure in steps (e.g., 10 bar -> 7 bar -> 4 bar), the pressure at the vena contracta of each stage stays above the vapor pressure, preventing damage.

Gas Service: Choked Flow

In gas service, as the pressure drop increases, the velocity increases. Eventually, the gas velocity at the bore reaches the speed of sound (Mach 1). This is Choked Flow (or Critical Flow).

Once flow is choked, lowering the downstream pressure further does not increase the mass flow rate.

Application: This phenomenon is utilized in "Blowdown Restriction Orifices." During an emergency depressurization, an RO ensures that the flare header is not overwhelmed by limiting the maximum flow rate to the sonic velocity of the gas.

8. Industrial Applications

The practical deployment of these devices is vast. Here are specific scenarios where each is indispensable.

Orifice Plate Applications

- Custody Transfer: Measuring natural gas volume sold between pipeline companies (requires high accuracy and AGA 3 compliance).

- Process Control Loops: Providing flow feedback to a PID controller regulating a control valve.

- Steam Metering: Boiler efficiency monitoring using boiler feedwater and steam output flow rates.

- Material Balance: Tracking mass entering and leaving chemical reactors to ensure reaction efficiency.

Restriction Orifice Applications

- Pump Minimum Flow (Recirculation): Installed in a bypass line to ensure a centrifugal pump always has flow, preventing overheating when the main discharge valve is closed.

- Blowdown Systems: Limiting the rate of depressurization in a vessel during a fire case to prevent brittle fracture due to Joule-Thomson cooling.

- Controlled Pressurization: Used in bypass lines around large isolation valves to equalize pressure slowly before opening the main valve.

- Snubbers: Protecting pressure gauges from pressure spikes/water hammer.

9. Standards, Installation, and Maintenance

Standards

ISO 5167 is the global bible for differential pressure flow measurement. It dictates the geometry, surface roughness, and installation requirements for orifice plates.

For Restriction Orifices, there is no single governing standard like ISO 5167. Sizing often relies on R.W. Miller's "Flow Measurement Engineering Handbook" or Crane Technical Paper 410.

Installation: The Straight Run Requirement

FE: Because FEs rely on a stable velocity profile for accuracy, they require significant upstream and downstream straight pipe lengths (e.g., 10x to 44x pipe diameter upstream, depending on pipe fittings). Flow conditioners (tube bundles) can be used to reduce this length.

RO: ROs are less sensitive to flow profile since they are energy dissipaters. However, sufficient downstream length is required to allow turbulence to settle before the fluid enters susceptible equipment like control valves or heat exchangers.

Maintenance

Maintenance is essentially "inspection."

FE Inspection: The sharp edge must be checked. A nick or rounding of the edge by just a fraction of a millimeter can cause errors of >1%. The plate must be flat; bowing causes errors.

RO Inspection: Checked for bore enlargement (erosion). If the bore of a restriction orifice enlarges, it flows more than calculated. In a pump recirculation line, this means wasting energy. In a blowdown line, this could mean overloading the flare.

10. Conclusion

The Orifice Plate and the Restriction Orifice illustrate a beautiful duality in engineering: one seeks to observe the flow with minimal intrusion, while the other seeks to control the flow through brute force restriction.

For the Process Engineer, the choice is never ambiguous. If the goal is data, accuracy, and minimal permanent pressure loss, the Orifice Plate is the tool of choice. If the goal is safety, pressure reduction, pump protection, or controlled depressurization, the Restriction Orifice is the unsung hero.

Mastery of these components—knowing when to use a multi-stage RO to prevent cavitation, or how to install an Eccentric FE to handle wet gas—distinguishes the novice from the expert. As industries move toward digital transformation, these simple, robust mechanical devices remain the foundational bedrock of safe and efficient plant operation.